At the Arsenale in Venice stands a white marble lion whose story stretches from the classical world to the decline of the Ottoman Empire, via the Vikings. Around three metres in height, the Piraeus Lion was one of a pair of statues that stood guard – probably as a fountain – at the Athenian port of Piraeus, having been sculpted circa 360 BC.

Originally stationed at the Piraeus harbor near Athens, the two lions were transported to Venice in 1687 by Francesco Morosini after a successful campaign against the Turks. From the beginning it was noticed that one of them had strange markings carved into its shoulders, apparently some kind of writing. Nobody knew the meaning of the writing, however, or even what language it was. Only much later did scholars recognize the markings as runes. It was a puzzling discovery. What were Scandinavian runes doing on a marble lion taken from a Greek port? The inscribed words themselves would answer the question.

It is only a hundred years later that the inscriptions were identified as runic by Johan David Åkerblad, Swedish diplomatist. However, already by that time several fragments of the carvings were destroyed by erosion, so that deciphering and translation were barely feasible. Attempts to read the texts abound, but hardly any one of the interpretations might be relied upon.

The conclusion reached was that at some point in the 11th century travelling Vikings had carved the runes as a form of graffiti, not unlike the Viking inscriptions at the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Several attempts to decipher the inscription – no easy task – followed, the most accurate of which is considered to be Erik Brate’s interpretation of 1914, which contains an explanation of the inscriptions thus:

The statue, which is made of white marble and stands some 3 m (9 ft.) high, is particularly noteworthy for having been defaced some time in the second half of the 11th century by Scandinavians who carved two lengthy runic inscriptions into the shoulders and flanks of the lion.The runes are carved in the shape of an elaborate lindworm dragon-headed scroll, in much the same style as on runestones in Scandinavia. The carvers of the runes were almost certainly Varangians, Scandinavian mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Emperor.

Originally stationed at the Piraeus harbor near Athens, the two lions were transported to Venice in 1687 by Francesco Morosini after a successful campaign against the Turks. From the beginning it was noticed that one of them had strange markings carved into its shoulders, apparently some kind of writing. Nobody knew the meaning of the writing, however, or even what language it was. Only much later did scholars recognize the markings as runes. It was a puzzling discovery. What were Scandinavian runes doing on a marble lion taken from a Greek port? The inscribed words themselves would answer the question.

It is only a hundred years later that the inscriptions were identified as runic by Johan David Åkerblad, Swedish diplomatist. However, already by that time several fragments of the carvings were destroyed by erosion, so that deciphering and translation were barely feasible. Attempts to read the texts abound, but hardly any one of the interpretations might be relied upon.

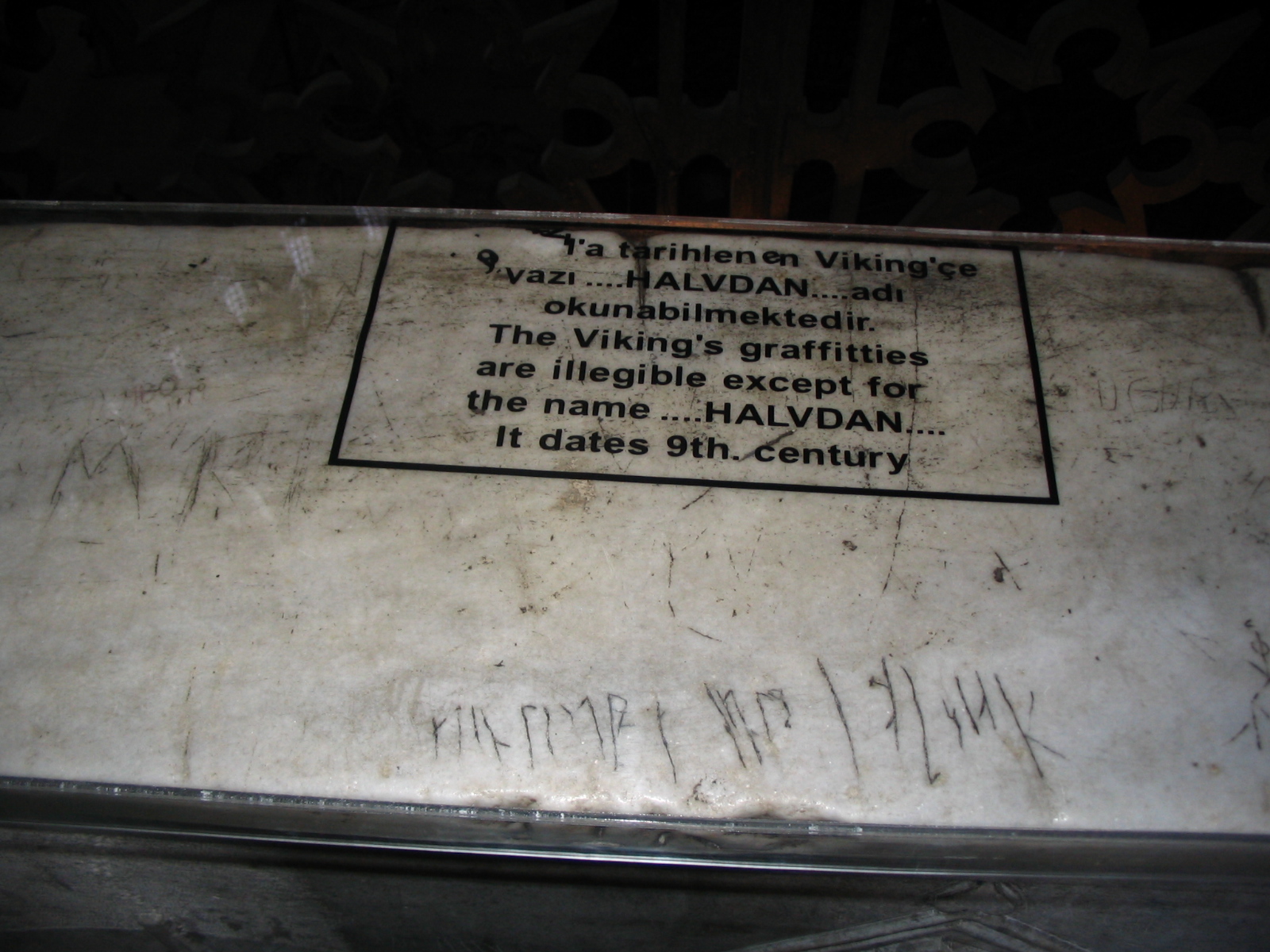

The conclusion reached was that at some point in the 11th century travelling Vikings had carved the runes as a form of graffiti, not unlike the Viking inscriptions at the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Several attempts to decipher the inscription – no easy task – followed, the most accurate of which is considered to be Erik Brate’s interpretation of 1914, which contains an explanation of the inscriptions thus:

|

|

The statue, which is made of white marble and stands some 3 m (9 ft.) high, is particularly noteworthy for having been defaced some time in the second half of the 11th century by Scandinavians who carved two lengthy runic inscriptions into the shoulders and flanks of the lion.The runes are carved in the shape of an elaborate lindworm dragon-headed scroll, in much the same style as on runestones in Scandinavia. The carvers of the runes were almost certainly Varangians, Scandinavian mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Emperor.

|

| Hagia Sophia Viking graffiti |

0 comments:

Post a Comment